By Emily Sims

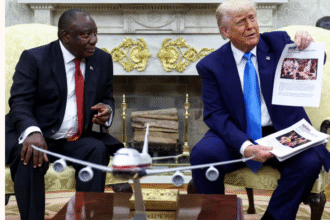

Washington D.C. – The United States is intensifying its competition with China in Africa by placing a renewed emphasis on trade and investment, signaling a shift from traditional aid-based diplomacy. The State Department has introduced a new performance metric for American ambassadors in Africa, evaluating their success based on the number of business deals they facilitate, reflecting the administration’s focus on a “trade, not aid” approach.

This new strategy comes as the US seeks to counter China’s significant influence on the continent, particularly its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). According to Troy Fitrell, a senior US official for the Bureau of African Affairs, the administration has already secured 33 deals worth US$6 billion across the continent within its first 100 days. He outlined the new commercial diplomacy strategy as one that “focuses our efforts on the countries where US companies want to do business and where the data shows we ought to do business.”

However, the shift has drawn criticism, particularly in light of other policy changes. Critics point to the restructuring of USAID and the scaling back of other aid programs, as well as the potential dismantling of the Millennium Challenge Corporation, which has invested over US$10 billion in Africa since 2004. These moves, coupled with trade tariffs, raise concerns that the US may be retreating from its commitment to the continent.

“[Eliminating] USAID removes the aid component, but getting US businesses to step up with the trade component is not obvious,” said Cameron Hudson, a former US official and senior associate at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies. He emphasized the existing perception of Africa as a high-risk investment environment for American businesses, further noting that, unlike China, the US government cannot directly mandate private sector investment.

Experts highlight the contrast between the US approach and China’s long-standing, pragmatic, and strategically-oriented foreign economic policy towards Africa. While the US has enacted the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), exports to sub-Saharan Africa remain less than 1% of total US trade, a figure unchanged for over two decades. In comparison, China surpassed the US as Africa’s largest trading partner in 2009, with trade volume reaching approximately US$295 billion last year, compared to the US’s US$71.6 billion.

The US is particularly focused on challenging China’s dominance in infrastructure development, with Fitrell stating that the US will invest in commercially viable projects, explicitly distinguishing them from what he described as “vanity projects or infrastructure built by the Chinese government.” He pointed to the US$4 billion Lobito Railway Corridor and the US$4.7 billion LNG project in Mozambique as examples.

However, some experts believe that these projects are insufficient to rival China’s broader and more systemic investments under the BRI. Carlos Lopes, a professor at the University of Cape Town’s Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, stated that US efforts, while pivoting towards commercial partnerships, “have never matched those of China’s sustained, state-coordinated engagements across the continent.”

Lopes concluded that if the US intends to achieve meaningful “trade, not aid” outcomes, it will need to rethink its current strategy, rebuild instruments for long-term investment, and engage with African priorities beyond purely transactional deals. The success of the new ambassadorial performance metrics, therefore, remains to be seen, hinging on the ability of the US to incentivize private sector investment and align its commercial interests with the development needs of African nations.